III. CHALLENGES FOR SPATIAL POLICIES |

1. The BSR in global comparison

Large area – small population

Forests

and arable land make up most of the land area of the BSR. Other prominent

features include large bodies of fresh water, as well as glaciers and tundra.

Built-up areas comprise less than 1% of the total land area.

The distance between its northern and southern extremes corresponds to the distance

between London and Istanbul.

|

Physical distances within the BSR

|

The BSR land area (2.4 m. km²) is nearly three-quarters of the area of the EU. The average population density (44 inhabitants/km²) is low when compared with the EU.

Actor of global importance

The BSR plays a significant role in the world economic system. In 1998 the Gross National Product of all 11 BSR countries to which the Baltic Sea functions as a gateway (incl. the whole of Germany and Russia) was some 40% of the GNP for the EU.

The BSR hosts ten metropolitan areas with populations of 1 million or more.

Some E-BSR countries have made considerable progress in the transition from centrally planned to market economies. Their markets are growing up to three times the world average.

The BSR is home to well-known companies and product brands. It hosts more multinational companies per capita than most other regions of the world.

The BSR is a rapidly growing destination of foreign direct investments. It is the leading IT and Telecom region of Europe. The cellular phone penetration is the highest world-wide.

The air communication network is improving rapidly. There are now international direct flights to more than 30 destinations within the region.

For centuries, the BSR has been a natural trading area. Ferries and freighters constitute an extension of the road and railway networks. Several ports function as gateways to hinterland markets of Eastern Europe and Russia. Some 45% of total foreign trade of Russia pass through BSR harbours.

But many of these strengths of the region are unevenly distributed within the BSR, with high differences between BSR countries.

Unity and diversity

The BSR is maybe the least homogenous region in Europe. This creates a demand for internal cohesion and is a source of particular market potentials.

The BSR spans arctic to temperate climate zones. Its 103 million inhabitants live in 11 different countries or parts thereof, in which as many major languages are spoken.

Forms of government include three parliamentary monarchies, two federal states and six republics. Four countries are EU members, four are negotiating membership, one country is a member of the EEA. Two countries are not members of these organisations, but co-operate closely with them.

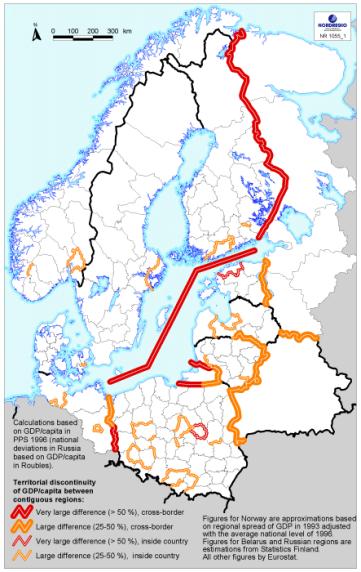

The span of GDP per capita between different BSR countries is substantial.

Well developed education and living cultural heritage

|

The BSR in global comparison

Note: GNP (Gross National Product) figures differ from figures from national statistics, as they were converted according to the Atlas method for better comparability. The Atlas conversion method involves using a three-year average of exchange rates to smooth the effects of transitory exchange rate fluctuations. As exchange rates do not always reflect international differences in relative prices, GNP/capita estimates are also converted into international dollars using purchasing power parities (PPPs). PPPs provide a standard measure of real price levels between countries. The PPP conversion factors used here are derived from the most recent round of price surveys-covering 118 countries-conducted by the International Comparison Programme (ICP)

|

Cultural links are strong internally and externally since the middle ages. Cultural heritage makes the BSR a region of a specific identity in diversity, attractive to tourists and business. The BSR is world-wide among the regions with the highest density of opera houses. Nordic countries have developed university networks even in peripheral areas.

The education level is high in the BSR. It is a region of competence in natural science and technology, but as well in the cultural ‘industry’. The BSR as a whole spends more on R&D as a percentage of GDP than most other countries in Europe. But again, national differences are very high ranging from 0.5 to 3.9%.

There is a fruitful collaboration between industry and academia, particularly in Nordic countries, forming the basis for development of several large firms.

2. Socio-economy

|

Challenges regarding the BSR global position

Enhance the global competitiveness of the whole BSR, spreading the strengths of successful sub-regions;

Maintain diversity while promoting unity.

|

Structural change is the overwhelming feature of this region. As any other region, the BSR is confronted with opportunities and threats resulting from the globalisation process and the upcoming knowledge and information society, with stagnation or decline of some traditionally important economic sectors.

But countries in the E-BSR face additional structural changes: They move from centrally planned to market oriented economies. In parallel, some transition countries prepare for EU membership, while others have to see how to adapt to a situation where most partners will be within the EU, while they themselves remain outside.

|

Socio-economic challenges for spatial policies

Enhance the economic flexibility to benefit from chances of economic integration and knowledge-based activities;

Enhance new economy activities;

Avoid economic dis-integration due to EU enlargement with some BSR countries left outside;

Counteract social segregation between winners and losers of structural change;

Find sustainable ways to deal with growing mobility;

Promote the capabilities of local and regional self-government to cope with their expanded responsibilities;

Enhance participation of numerous actors and population groups at all levels;

Develop a moderating and frame setting role of central government.

|

W-BSR countries have managed with different success to benefit from the new economy. In general, the Nordic BSR is a forerunner in the information society, generating spill-over opportunities for other parts of the region.

In many parts of the E-BSR, structural change was coupled with significant losses in living standards of large proportions of populations.

Most BSR transition countries have started economic recovery. But in aggregate, many of them have not reached again previously existing welfare levels. Life expectancy has declined in many parts of the E-BSR (except in Poland), and knowledge advantages have sometimes been lost.

Trade directions and traded commodities have changed towards further integration into the world economy.

A common feature of all changes is growing mobility. Population has migrated, from newly independent countries to their native home countries, from rural to urban areas, from smaller to metropolitan cities. Commuting has increased strongly, as well as telecommunication. This has contributed a new dimension of freedom. But it has also caused problems of infrastructure and environment.

Freight transport demand has become fragmented, from bulk to small consignments. This led to growing use of road vehicles and a decline of railways services.

Privatisation has given public institutions a new role which focuses on mobilisation and coordination of actors instead of preparing and implementing plans.

Democratisation has strengthened the role of local and regional self-government. This again provoked a new role of central government, to rely on subsidiarity and participation instead of central ruling. It led to growing qualification demands at these levels, not always met yet.

3. Environment and nature

Environmental trends are closely linked to economic structural change. The decline of ‘old economy’ activities has reduced pollution, particularly in transition countries.

The new economy production generates less environmental pressure. But globalisation, economic recovery and growing mobility induce strong growth of energy consumption for expanding production and higher transport volumes – mainly on roads.

Economic recovery in eastern Europe's agriculture threatens to lead to growing pollution from agriculture using growing quantities of fertilisers, insecticides etc. This counteracts the positive trend of the new economy, if no counter-measures are taken.

Ground and surface water and soils are, in many parts of the BSR, under environmental pressure from insufficiently treated municipal and industrial wastewater, from air pollution and from intensive farming. Though progress has been made in recent years, water bodies in major parts of the BSR - surface and underground - are still exposed to high pollution loads from municipal and industrial waste water and from intensive agriculture.

Growing environment consciousness has supported efforts to promote energy efficiency, to reduce emissions, to enhance regenerative energy production. But support to environment friendly public transport has not been successful, with few exceptions.

Declining agriculture in some regions may weaken the potential to preserve highly appreciated natural and cultural landscapes. But there is also the chance to develop more natural landscapes.

|

Population change in BSR cities>10 000 inhabitants during the 1990s

|

|

Challenges regarding nature and environment

Link protection with development;

Channel pressure from development of human activities on nature;

Counteract the trend for growing transport on roads; enhance more environment friendly transport modes;

Promote coordinated spatial development policies across administrative levels;

Promote the networking of valuable nature areas to counteract fragmentation;

Make more use of financial instruments to support valuable nature areas;

Develop natural and cultural heritage together

|

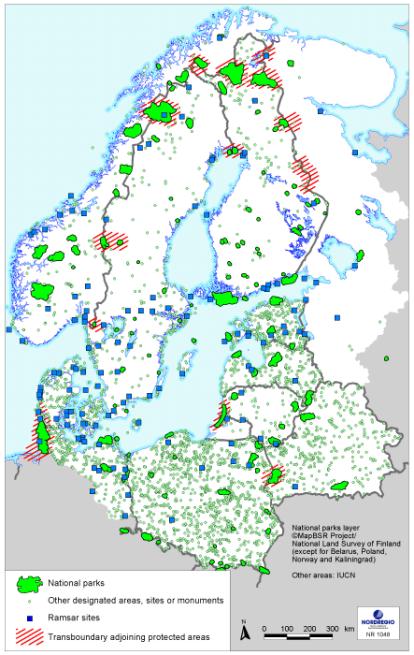

Threats to bio-diversity are of particular importance to the BSR, as this region still possesses large areas of rich flora and fauna. Commercial forestry, industrialised agriculture, growth of transport and urban sprawl generate pressure on these values.

Networking among valuable nature areas, including cultural landscapes, contributes to the preservation of bio-diversity. This requires new approaches linking development of areas with different sensitivity and different intensity of human activities. Network development must involve administrations of different sub-regions and of different levels.

4. Spatial structure

|

Challenges regarding internal structures of urban regions

Move from mono- to multi-core urban structures which combine decentralisation with strong public transport systems;

Promote sustainable internal urban structures;

Promote urban renewal and land recycling;

Support social integration.

|

Spatial trends have been analysed according to main components of the spatial system: settlement system; rural areas and cultural landscapes; coastal areas and islands; mobility and energy networks. On this basis, conclusions are drawn regarding spatial cohesion. More details on spatial trends are available in a separate background report.

|

Challenges regarding the settlement system

Raise the competitiveness of urban regions;

Counteract growth concentration at too few urban centres through accelerated development of urban centres in regions lagging behind.

|

4.1 Settlement system

Economic structural change and growing mobility have altered the development perspectives of cities.

New knowledge-based activities concentrate at few major urban centres. The transition process in south-eastern BSR countries

further enhances this concentration.

Large sub-regions with less competitive urban centres lag behind. Many urban regions in the BSR need to raise their competitiveness.

This holds true even for major cities depending too much on the traditional economy. It also applies to other 'secondary' city regions. Good examples of successful urban strengthening exist in the BSR.

Major challenges refer to the internal spatial structure of urban regions. Most of them are valid for other parts of Europe as well. But differences exist from country to country.

A suburbanisation trend creates growing pressure on valuable landscapes. It generates additional transport demand, mostly resulting in additional road traffic. Large shopping areas take away market potentials from old urban centres and affect the urban attractiveness as a whole. Multi-core urban development can help to alleviate these problems - within larger metropolitan regions, as well as in groups of smaller urban centres in other regions. This requires urban management.

Transition countries still have high-density urban land-use structures with a high share of public transport. But they need to move from mono- to multi-centric urban structures to maintain that strength.

Renewal of traditional city centres helps to maintain the attractiveness of whole city regions. Recycling of areas where traditional economic activities close down contributes to a rational economic use of land.

Large housing estates have begun to loose population due to low attractiveness and population migration to more prosperous regions. In some locations, there will be a growing need for pulling down, in others for revitalising such complexes.

Decay of old urban centres and of new large housing estates provokes unwanted social segregation, harming the stability of societies.

|

Challenges regarding mobility and energy networks

Promote environment friendly modes of transport;

Add to transnational infrastructure concepts corridor improvements relevant for regional development and for effective integration across the BSR and across the whole of Europe;

Support the functionality of ports as transport nodes;

Promote spatial structures which support public transport and energy efficiency;

Enhance the formation of a common energy market.

|

4.2 Mobility and energy networks

Growing mobility is a global trend also encountered in the BSR. High rates of increase in road traffic are further expected in transition countries. But in other BSR countries, too, this trend has not come to an end.

The potential for environment friendly modes of transport depends on spatial structures of cities and regions. But there is also a need to improve performance qualities of railways. This requires investments into railway infrastructure and rolling stock and more internal competition among different railway operators. Only then will the introduction of road pricing have a significant impact on modal split.

In some parts of the BSR (particularly in E-BSR), deficient transport infrastructure is a bottleneck to regional development, using the potentials from interregional integration. The improvement of some important transport corridors is not considered in national and transnational development programmes. Its need shall be demonstrated based on regional development analyses. A closer dialogue of spatial planning with transport sector institutions concerning transnational infrastructure development is required.

Maritime transport helps to alleviate pressure on land infrastructure. This environment friendly mode of transport has a dominant role in freight transport of the BSR. Growing hinterland traffic creates particular problems in port cities and hinterland links. Coordinated planning is required while maintaining undisturbed competition between ports. Organising intermodal transport chains with hinterland connections of port cities by rail, road and inland waterways shall be further improved.

A common energy market does not exist yet in the BSR. It would help to enhance energy efficiency. Market integration requires further deregulation, new linking infrastructure, and harmonisation of technical systems.

Combined electrical power plants supplying central heating are well developed in the BSR. But urban sprawl tends to reduce the potential for this environment friendly concept. Multi-core urban structures (= decentralised concentration) help to counteract this threat.

4.3 Rural areas and cultural landscapes

Rural areas in commuting distance from major cities benefit from spill-over of the latter. But they run the risk of fragmentation through urban sprawl squattering into natural and cultural landscapes. The result is a loss of their rural identity. Integrated urban-rural planning is required.

|

Challenges in rural areas and cultural landscapes

Counteract urban sprawl;

Strengthen functionality of cities as growth engines in rural areas;

Develop valuable natural and cultural landscapes together in a network perspective, linking protection with development and balancing different goals;

Develop cultural assets as a source of income;

Promote integrated rural development which joins urban and rural elements and which links different sector measures.

|

Of concern are rural areas far from major urban centres, with a weak own urban system, with high-density population and fragmented, low-productivity, farming. This type of areas exists in major regions of E-BSR in Poland and Lithuania. They combine expected losses in agriculture employment with low capacity to develop new job opportunities.

Strengthening of urban functions is required there, to counteract interregional migration. Such migration would further reduce the functionality of these areas, and make a decent level of service provision still more difficult.

A similar problem arises in large areas with low-density population and only small urban centres, frequently found in the northernmost parts of Nordic countries, in the Russian Federation (Republic of Karelia), in Estonia and Latvia.

There is a risk that policies concentrate on more prosperous regions and neglect problems of less favoured ones.

|

Challenges regarding coastal areas

Balance ecological, social and economical goals for development of coastal zones, including areas of different nature sensitivity and of intensive human activities;

Achieve integration between land and sea-side developments;

Promote co-ordination across sectors and across administrative-boundaries;

Link ICZM to statutory spatial planning.

|

Rural areas in the BSR contain valuable cultural landscapes, often mixed with valuable nature areas. These areas are important to preserve cultural identity and spatial attractiveness. They are characterised by a strong desire to protect heritage, but also to participate in growing prosperity of respective countries and regions. They are not defined by administrative boundaries, and therefore require specific planning approaches.

4.4 Coastal areas

Coastal areas play an important role in the BSR, with a concentration of human activities – cities, ports, industry, agriculture, tourism – and of sensitive nature – wetlands, erosive shores, archipelagos. Seaside activities have an influence on coastal zones, including shipping, mining, bathing, fishing and military uses.

An integrated development of these different demands is largely missing due to sectoral thinking and insufficient coordination across administrative borders. Integrated planning for coastal zones which balances different interests has not yet been adequately linked to statutory planning routines.

|

Challenges regarding BSR islands

Develop the islands’ economies while maintaining and activating their cultural identity;

Reduce accessibility disadvantages through enhanced use of telecommunication and improved travel links (ferries, air services);

Develop new economic sectors less dependent on travel cost (tourism, other services);

|

4.5 Islands

The BSR has a high number of islands, including archipelagos with mostly not inhabited islands.

The inhabited bigger archipelagos and islands are in a similar position as rural areas distant from major urban centres. Tourism is one of their potential sources of income. Information and cultural activities are other promising sectors, while traditional fishery is declining.

Island populations are characterised by a strong identity. By enhanced participation, this asset can contribute to the process of economic restructuring.

5. Spatial cohesion

The BSR is a region of extreme spatial disparities in welfare levels. The span of GDP per capita between different BSR reaches a ratio of 1:6 (see chapter III-1) measured at purchasing power. Disparities in the level of salaries are even wider.

Cross-border disparities are particularly strong between, on one side, Russian BSR areas and Belarus, and on the other side Finland, Sweden and Norway, with a tendency to grow.

Other indicators confirm the stated disparities between BSR countries, such as direct foreign investment per capita, research & development expenditure, concentration of new economy activities, or location of multinational companies.

Not as big, but still considerable disparities also exist within countries, particularly between national growth centres and more peripheral regions. Statistical evidence is limited here, but again, there seems to be a tendency of growing interregional disparities in major parts of the BSR.

A particular threat to cohesion is the existence of large areas with relative high population density, strong dependency on low-productivity agriculture and weak urban system (as discussed above under ‘rural areas’).

A third issue for cohesion is missing high-quality linking infrastructure and public transport services to bind southern BSR coastal areas together, and to link Baltic States to Western Europe.

6. Transnationality in national spatial plans

The majority of national spatial development plans and concepts of BSR countries have been prepared only recently. They pursue largely consistent objectives.

They promote a balanced settlement system enhancing growth centres. They seek to make more use of cities as growth engines in regions lagging behind. Urban networking is advocated in most countries. Structures of urban regions are sought to enhance sustainable development which avoids social segregation, which strengthens public transport systems, and which facilitates combined power & heating energy plants.

As regards the infrastructure system, transition countries put emphasis on improving infrastructure quality and capacities. A shift towards environment friendly transport modes is generally favoured. Intermodality is seen as an important tool, as well as spatial structures based on ‘decentralised concentration’.

|

Challenges regarding BSR spatial cohesion

Counteract growing disparities across BSR borders regarding innovation and welfare;

Support spatially more balanced growth within countries;

Ensure transport infrastructure improvements necessary for regional competitiveness and pan-Baltic integration.

|

In rural areas, strengthening of urban centres is considered important. This includes networking of cities, improvements of links between cities and better accessibility of urban services for rural populations.

|

Challenge for national spatial development plans

Promote the explicit consideration in national spatial plans of linkages with corresponding plans in neighbouring countries.

|

For the green system comprising natural and cultural landscapes, all BSR countries consider it important to maintain cultural heritage. The possibility is seen to combine this with the promotion of development.

The concept of sustainable development is also highlighted as an integrative task for coastal zones. This is particularly important where strong development pressure coincides with sensitive nature.

Transnational aspects are not adequately reflected in national plans, with the exception of transport infrastructure. Only in some cases, also border areas and coastal zones are addressed as transnational issues.

Thus, most national plans don’t show systematically linkages with neighbouring countries for all relevant aspects of the spatial system. Cross-border plan interdependencies needs to be made more transparent.

This is particularly relevant for green networks – comprising areas of different development potentials and natural sensitivity – and for coastal areas, but also for greater development zones extending across borders.